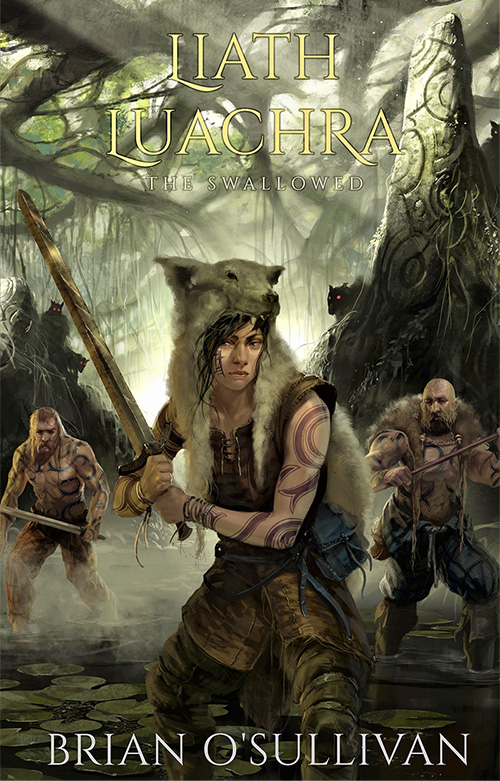

Osraighe: Ireland’s shadowy centre, a desolate region of forest, marshes and mountainous terrain where unwary travellers are ‘swallowed’ and never seen again.

Caught up in an intra-tribal conflict when her latest mission turns sour, the woman warrior Liath Luachra finds herself coerced into a new undertaking. Dispatched to Osraighe to find a colony of missing settlers, she must lead a mismatched group of warriors, spies, and druids through a land of spectral forest, mysterious stone structures, and strange forces that contradict everything she knows of the Great Wild.

Haunted by a dead woman, struggling to hold her war-band together, Liath Luachra must confront her own internal demons while predators prowl the shadow between the trees …

Awaiting their moment to feed.

Liath Luachra: The Swallowed is the second stand-alone book in a spin-off series from my original Irish mythological cycle, the Fionn mac Cumhaill Series. Although originally envisaged as a minor character in that series, the woman warrior Liath Luachra’s compelling personality meant she became a dominant force in every book. This particular novel is the direct result of a stream of emails from readers demanding more background to the character.

As you can see, ancient Ireland wasn’t exactly the most comfortable of spots. The more complex stone monuments that pepper the countryside were there two thousand years before the Celts turned up. By the 2nd century, the majority of the land was challenging to traverse in that it was heavily forested, the midlands were reeking swamp and the island itself was sparsely populated.

And that’s not even counting Na Torathair, misshapen creatures lurking in the darkness to snatch the unwise and unworthy.

Liath Luachra: The Swallowed unsheathes its sword on 1 July 2018 and is available for pre-order on Amazon. A limited number of ARCs are available to reviewers who like to dip their toes in new worlds … that are remarkably ancient.

***

The Mandatory Excerpt!

In this excerpt, Liath Luachra, the Grey One of Luachair, is awaiting a meeting with the Mical Strong Arm, rí (Chieftain) of the Uí Bairrche tribe. While waiting, she comes across his daughter.

——————————————————————————————————————–

Mical Strong Arm’s daughter looked up from her play, her lips compressed in a prim expression of suspicion and annoyance at the intrusion. Skinny and pale, she had straw-coloured hair and her wide blue eyes assessed the newcomer with cool disdain. The Grey One thought her quite small for her age, for Dalbach had told her the girl had ten or eleven years on her.

Ignoring the cold reception, the woman warrior reached over to pluck one of the dry mud cakes from the stone, raised it to her nose and pretended to sniff it.

‘Mmm. That smells good. Shall I eat the cake?’ She licked her lips in exaggerated appreciation of the prospect. ‘Num-num.’

The girl stared, her expression a mixture of irritation and incomprehension. ‘You don’t eat mudcakes. They’re … They’re mud!’ She regarded the woman warrior in exasperation, her jaw jutting out with comical self-righteousness.

‘My brothers and I, we made mudcakes. We made the best mudcakes in Luachair. People came from all over to try them.’

‘Really?’ Despite her suspicions, the girl’s expression softened. Her features were quite delicate the Grey One noted, the small nose and distinct cheekbones probably due more to her mother than her father.

Liath Luachra shook her head. ‘No,’ she confessed. ‘Our cakes were terrible. They were so bad everyone avoided Luachair. Even the rats wouldn’t eat them.’ She screwed her face into an exaggerated grimace causing the girl to giggle effusively.

‘Does your father beat you?’ Liath Luachra asked.

The girl’s eyes widened. ‘No! He …Why would he …?’ She went silent, too confused to articulate what was clearly an alien concept.

‘You’re not afraid of him?’

‘Of my father? Of course not.’ She puffed up her tiny chest. ‘I’m not afraid of anything. I’m not … Well, except for the black shadows at night of course.’ Her face took on a worried expression.

‘You don’t need to be afraid of the black shadows,’ the woman warrior reassured her. ‘That’s simply what happens when the colours of the world go to sleep.’

This time the girl stared at her, completely intrigued. ‘The colours of the world go to sleep?’

‘Yes. Every night, Father Sky opens his bag, gathers up the colours of the world and sets them all inside. When the colours have gone, there’s nothing left in the world but black, the colour of night, the colour even Father Sky has no use for.’

‘Why does Father Sky put them in his bag?’

‘Because colours have to rest too. Just like us. In Father Sky’s bag they can sleep the good sleep so that when he releases them again the next morning, they’re refreshed and new and shine as brilliant as the day before.’ She made a loose gesture with one hand. ‘Except for the dull days when they didn’t get enough sleep.’

The Uí Bairrche girl sat back on her haunches, her lips pursed in thought as she considered the logic of Grey One’s explanation. ‘Is that true?’ she asked at last.

‘I don’t know for sure,’ Liath Luachra admitted. ‘But I think so. My mother told me that story and she wasn’t the kind of person to tell lies.’

The girl looked at Liath Luachra with fresh interest. ‘Lígach’s the name on me,’ she said at last, the revelation apparently a formal confirmation of the Grey One’s approval. ‘What name do you have on you?’

‘I don’t have a name on me. Not anymore.’

Lígach’s nose crinkled in adult-like incredulity. ‘That’s silly. Everyone has a name.’

‘Not me. Not a real name. I lost my real name … long ago. Back when I was a little girl. Just a few years older than you.’

The girl shook her head. ‘That doesn’t make sense. How can you lose your name?’

The Grey One looked at her, silent for a moment. ‘I’m not sure,’ she said at last and gave a shrug. Perhaps …’ She paused. ‘Perhaps it fell out of my pocket.’

Lígach giggled. ‘That’s silly.’

The Grey One looked down at the ground. ‘Perhaps,’ she said again.

Lígach nodded with certainty, as though her own answer resolved that particular conundrum. ‘Are you here to speak with my father?’

‘I am.’

‘Is he sending you away to An Díthreabh Uaigneach [The Lonely Land] too?’

Taken by surprise, the woman warrior pulled back a little. ‘Yes.’

The girl leaned forward in a conspiratorial manner, pressing her lips close to the woman warrior’s ear. ‘When you’re in The Lonely Land,’ she whispered urgently. ‘Stay away from the dark shadows. The dark shadows eat you up.’

Liath Luachra blinked and regarded Mical Strong Hand’s daughter in consternation but before she could question her further, a loud voice called out to her rear. Glancing back over her shoulder, she saw Dalbach standing in the doorway of the stone hut, waving urgently for her to join him.

‘Grey One! Come. Mical Strong Arm and the others are waiting.’

As the woman warrior got to her feet, he disappeared inside again. ‘I have to go,’ she told the Uí Bairrche girl. Thank you for talking with me.’

Lígach nodded again, apparently knowing better than to interfere in her father’s business. ‘Remember,’ she said. ‘When you’re in the Lonely Land, stay away from the dark shadows.’