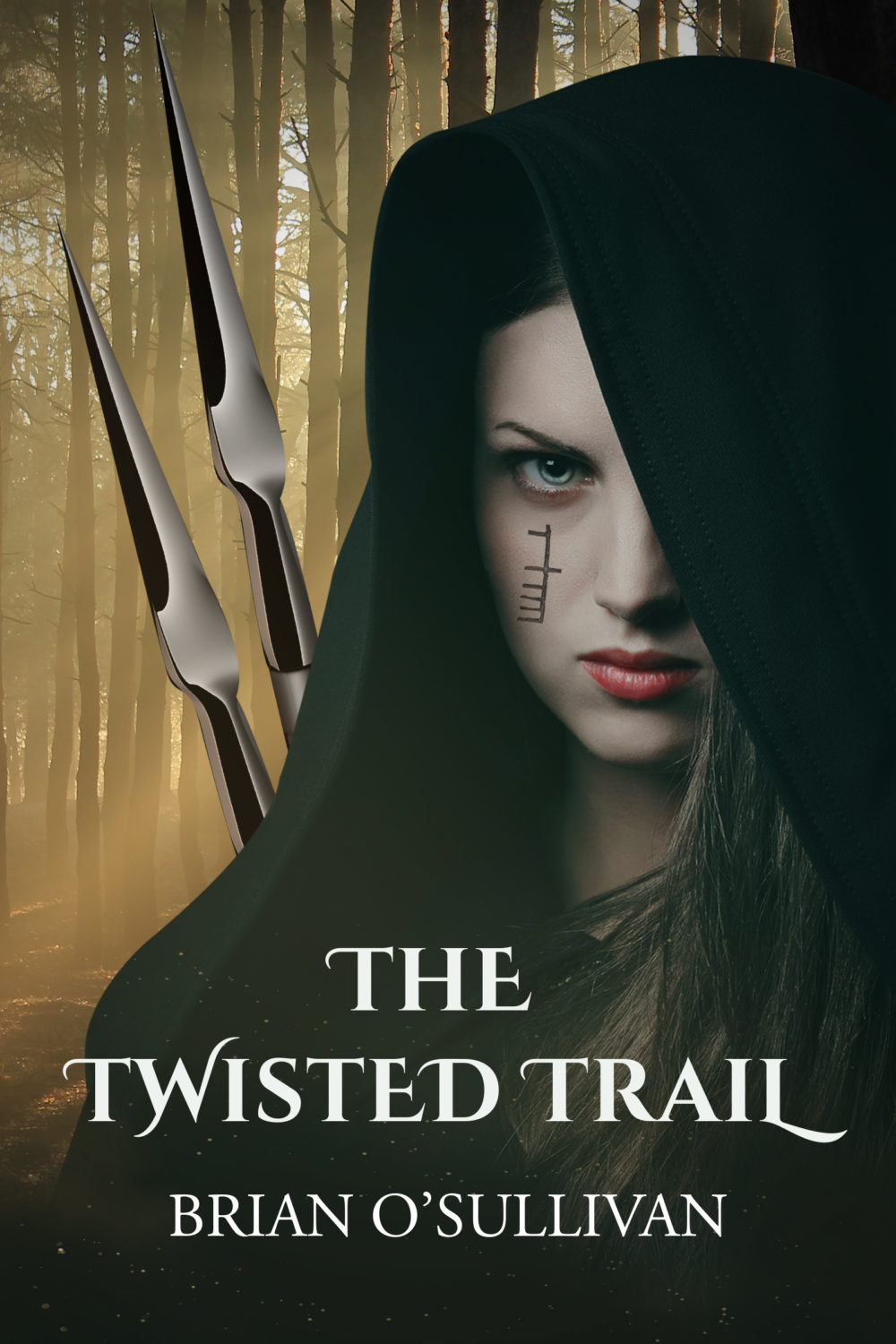

It’s been a hectic few weeks but the next tale in the Fionn mac Cumhaill Series is finally available.

FIONN: THE TWISTED TALE is a short story set four years after the events in the last book in the series (FIONN: The Adversary).

This story is only available in Kindle form (mobi) or in ePUB from (i.e. Apple, Kobo, Nook etc.) in the “Books” section of the Irish Imbas website (HERE). It’s unlikely to be released anywhere else.

THE STORY

This tale involves the woman warrior called Liath Luachra. While out hunting in the Great Wild with seven year-old Rónán and fifteen year-old Bran, she comes across the tracks of a fian (old Irish word for ‘war party’) hunting a solitary traveler who seems bound for the Bládhma hills where Ráth Bládhma (the settlement of Bládhma and Liath Luachra’s home) is located.

The following is a taster for the full story which sits at about 11,500 words. The accompanying glossary may also be useful:

An Poll Mór – The Big Hole (a cave refuge)

Clann Morna – A tribe

Fian – A band of warriors or war party

Fénnid – a member of a fian. The noun can be plural or singular)

Óglach – A young, unblooded warrior (plural: Óglaigh)

Ráth Bládhma – A settlement (literally, the ráth of Bládhma)

A full pronunciation guide is available at the FIONN mac Cumhaill Series Pronunciation Guide

THE TWISTED TRAIL

It was a death-sun that revealed the strangers’ tracks south-east of the Bládhma mountains. Sliding in on the heel of dusk, its rare, slanted glare cast a bloodstained hue that illuminated the wide spread of footprints. Liath Luachra, the Grey One of Luachair, regarded them in silence. In all her years travelling that territory, she’d never once encountered evidence of another person’s passage. To find such a number and such a diversity of tracks in that rough and isolated area therefore, was enough to make her gut clench in unease.

Kneeling beside the nearest footprint, she brushed a thick strand of black hair from her face while keeping one wary eye on the surrounding forest. Because of the dense vegetation, there was little enough to see; a dark wall of tall oak trees climbing the ridges to the north and south, the distant blur of the Bládhma mountains peeking above the canopy to the east but no sign of movement or anything else out of the ordinary.

Reassured at the absence of any immediate danger, she bent closer, probing the footprint’s shallow depth with the fingers of her right hand. Conscious of the ruddy evening sky fading to grey, she scraped a piece of dirt free, raised it to her nose and sniffed.

It smelled, naturally enough, of earth. Of The Great Mother’s damp breath.

Tossing the gritty residue aside, she wiped her hand on the leather leggings that hugged her haunches and regarded the two boys standing nervously off to her right. Bran, with fifteen years on him, was more youth than boy but by nature tended to be the more solemn of the two. That sombre temperament was evident now in the furrows that lined his forehead and the nervous manner in which he chewed on his fingernails while studying the erratic mesh of tracks. The youth was visibly troubled by the prospect of strangers in Bládhma territory. Old enough to remember the brutal murder of his parents at Ráth Dearg more than a decade earlier, he was certainly old enough to realise that incursions like this didn’t bode well for anyone.

‘Who are they, Grey One?’

The younger boy, the dark-haired Rónán, had little more than seven years on him but was decidedly more buoyant than his friend. Despite the weight of a wicker backpack across his shoulders – a burden made up of cuts of wild pig from a successful hunt in Drothan valley – he stared down at the scattered tracks with unbridled excitement at such a novel discovery.

The woman warrior shrugged dispassionately. ‘Read the story in the Great Mother’s mantle. Read what the earth shows you and tell me what you see.’

The dark-haired boy reacted to the suggestion with his usual animation, nodding fervently to himself as he moved closer to the tracks. Ever keen to accompany the woman warrior on her forays into the Great Wild, he invariably responded to such tests of his woodcraft skills with enthusiasm. Crouching alongside her, his features fixed into a frown as he chewed on the inside of his cheek in unconscious mimicry. His long hair was held from his eyes by a leather headband but several strands had worked free, prompting him to brush at them with an irritated gesture.

Liath Luachra watched as his gaze fixed on the single footprint in front of him then transferred to the jumbled network of other tracks that surrounded them.

He’s just like Bearach. Happy and eager as an eager puppy.

She suppressed that thought immediately, burying it deep inside her heart, locking it in a dark and forlorn part of herself where she rarely dared to venture. Such memories were places best avoided, dangerous, fathomless chasms it was best not to shine a light down. And some things should never be exposed to the light of day.

‘There’s at least six or seven sets of tracks,’ noted Rónán. ‘The prints are spaced wide apart so they’re travelling fast.’

She nodded, pleased both by the keenness of his observation and the distraction it offered. ‘Yes.’

‘Headed east.’

She inclined her head to her left shoulder but made no response. That simple fact was plain to see from the direction in which the tracks were facing.

Sensing that he’d disappointed her, the boy tried again. ‘They’re men,’ he said warily, as though not entirely convinced of his own conclusion.

Again, easy enough to work out to see from the breadth of the imprints and the depths of their impressions.

‘Yes. But what else? What’s the pattern?’

Rónán looked at the prints once more. Unable to distinguish any obvious configuration, he threw an anxious glance towards Bran but the older boy had already turned away, directing his attention to other more distant tracks.

Realising that there’d be little succour from that quarter, the boy turned back to scrutinise the nearest imprint, bending to examine it more closely in the fading light. Despite staring at it intently for a time, his study produced no fresh intuition and finally, he raised his eyes to the woman warrior, conceding defeat with a frustrated shake of his head.

Liath Luachra had already moved away by then, taking up position at a nearby elm where she leaned casually against the trunk, her backpack pressed against the coarse bark to take some of the weight from her shoulders. She was looking towards the dying sun when she caught the movement of his head from the corner of her eye and, squinting against the ruddy light, she turned back to consider him with an impassive regard.

‘It’s a tóraíocht,’ she said. A pursuit. ‘A group of men are chasing another man, a solitary traveller.’ She gestured towards a particular line of tracks that had a visibly different appearance to the others. ‘See how those footprints look older? The edges are friable, the flat sections drier. All the other tracks are still damp because they haven’t fully dried out. That means they were made more recently, probably just a little earlier this afternoon.’

Rónán thought that explanation through for several moment before raising his eyes to regard her, his lips turned down in a frown. ‘But why are they chasing the single traveller?’

The woman warrior shrugged. ‘You know as well as I, there’s only so much of a story the Great Mother ever shares.’

Bran, who’d been observing their interaction in silence, cleared his throat and shifted his weight awkwardly from one leg to another. ‘Grey One. If they’re travelling east, they’ll strike Ráth Bládhma.’

Liath Luachra rubbed her nose and sniffed.

‘Just because the tracks here show them moving east that doesn’t mean their final destination lies in that direction.’ She gestured loosely towards the forested ridges north and south. ‘In this terrain it makes sense for the intruders to travel east. It’s likely they’ll drift to a different course once the land opens out.’

Bran kept his eyes lowered and made no response but she sensed he was unconvinced by the argument.

Sighing, the Grey One stepped away from the tree, grunting as the full weight of the backpack bore down on her shoulders. ‘Rest easy. Our own course to An Poll Mór follows their trail for a time yet. If they veer off the eastern path, we’ll know they’re no threat to Ráth Bládhma.’

‘What if they don’t veer off?’ asked Rónán.

‘That …’ The woman warrior gave another noncommittal shrug. ‘That is an issue we’ll address if we come to it.’