Back in the eighties in Ireland there was a famous ad going around from the Irish Development Authority (IDA), a government agency responsible for developing enterprise and attracting foreign investment. A component of one of their marketing campaigns, it consisted of a series of photos taken around some of our more famous prehistoric monuments (stone circles, passage graves, dolmens and so on). On this occasion though, those monuments were occupied by serious-looking Irish corporate types, standing around in business suits and looking about as comfortable as a funeral attendee in a clown costume.

The inference was pretty obvious of course. We’re the IDA! We are stable and dependable – just like the 2500+ year old prehistoric structures standing there in the background.

Needless to say, the IDA have long since been restructured and rebranded as ‘IDA Ireland’ which puts some of that arrogant hubris in perspective.

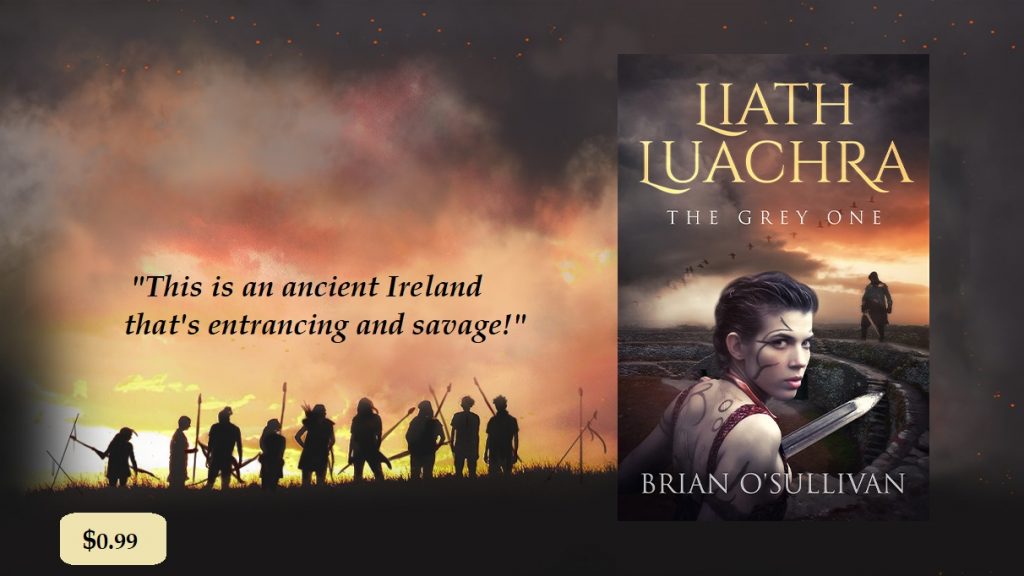

The IDA weren’t the only people drawn to the monoliths that dot the countryside, however. People have been visiting these monuments out of curiosity for centuries and to get a sense of perspective it’s good to remember that when the Celts first arrived in Ireland (sometime around 400-500 B.C.), those monoliths had already been standing for over a thousand years. It’s really no wonder the Celts were in such awe of them, an aspect I try to get across in my books (particularly the Fionn mac Cumhaill Series and the Liath Luachra Series).

Nowadays, Ireland makes a small fortune from cultural tourism associated with such sites, although such blatant commercial use would certainly have been frowned on until very recently. Up until the late-sixties or so, dolmens and standing stones were still very much localised features, respected and – in some cases – still feared due to the attribution of curses, hauntings and spirits from local folklore.

With the seventies and early eighties however, much of that reverence began to fade and in some cases a less … venerable approach to the monuments began to occur. Occasional complaints began to be heard about people (those feckin hippies!) dancing naked around some of the less-visited (but just as significant) monuments. Movies or television programmes would also throw up the old trope of “comely maidens dancing around a stone monument”. [Outlander anyone?’]

‘Dolmen Dancing’ was a throwaway term that I invented to reflect the societal change taking place over our generation with respect to the increased understanding of native history and the physical structures on our landscape associated with that. In a more practical sense of course, it also described what was actually happening as people got up front and personal with the monuments without fear of breaking any taboo. In fact, in some cases breaking taboos was actually the point.

My own, personal experience of Dolmen Dancing was up at the Poulnabrone Dolmen in Country Clare when I was part of a student group headed to Galway in a minibus for a sailing weekend. We ended up taking a slight detour to go and see the dolmen, arriving sometime in the early evening before it got too dark.

Given that we ‘d been drinking since noon, that we were in an isolated location without supervision and confronted by a famously revered monument … well, I’ll leave the rest up to your imagination. In my defence however, I will say however, that I am (of course) a fantastic dancer. No -one can compare after I’ve had a few scoops and my throwing of shapes on the dance floors of Cork is a matter of official record. I’m only sorry that my recall of the events at Poulnabrone is so hazy.

For years after the Domen Dancing incident, there were rumors floating around of compromising photos taken that day, stories in jest that invariably emerged after a fresh session of drinking. To be honest, no-one really believed them. Back in the late eighties, there weren’t any mobile phones – if they were, we didn’t have them. Cameras were also rare enough as they still took film and they were a pain to use after 3-4 pints. I did actually see three photos from that day but they weren’t exactly National Geographic material as the individual who took them had been just as steamed as the rest of us. One of the three he managed to take consisted of a close-up of his own foot (still wearing his boot), one was a picture of a section of rock that could have been anywhere in the country and the last was just a total blur. Needless to say, I wasn’t overly concerned.

Imagine my surprise earlier this year therefore, when I was browsing through a second-hand shop and came across a ripped magazine with the following images:

For a moment, I swear to God, my heart actually stopped. Even the haziness of the images seemed to fit my recollection of that particular day. I rummaged frantically through those ripped pages and it was only when I saw the photos had been taken by Robert Merrill (who?) that it finally dawned on me.

I wasn’t in them.

A bit more rummaging finally revealed the magazine’s cover.

So what the hell was the Arts in Ireland?

Who were the people dancing around Poulnabrone?

It took a bit of research work to find out what exactly was going on and it was only when I got home in September that I learned the Arts in Ireland magazine was a now defunct publication. Run in the seventies, it had been published by Charles Merill (the photographer) an American described online as a “self-made millionaire” and an “artist, gay activist and iconoclast”.

When living in Ireland, Charles had traveled to Poulonabrone in 73/74 and taken these photos (God knows with who but at least it wasn’t me!) and subsequently included them with a short written piece in a literary supplement of the 4th edition of The Arts in Ireland.

I read the associated piece by Merrill and, to be honest, it was quite surreal and typical of the romanticised spiritual tosh often written about Ireland during the 70s/80s by people from overseas. Essentially, it involves a story where he sees Isadora Duncan (an American dancer most famous for dying when her scarf got entangled in the wheel of a car – honestly, you couldn’t make this stuff up!) at Poulnabrone. Isadora talks a stream of nonsense about her Irish background (er….) and leaves Merill a message that “Ireland could become a cultural center in the world in the next few years.”

So there you go. All a bit surreal but the mystery was solved and, more importantly, my ass was – literally – out of the picture.

To be honest, I am a bit miffed by the discovery. Back in the late eighties, I’m sure I must have been all gung-ho and imagined I was doing something outrageously original. Now, of course, its clear someone else had already done it a decade earlier (and probably many others before that).

Either way, you’ll also be delighted to learn that the National Monuments Service (NMS) have taken past intrusions of Poulnabrone seriously and have since installed a high-tech security perimeter (a rope) around it. Here’s a picture of me studying it carefully with the son last year, while reliving old glory days! After careful assessment, I came to the conclusion that there was no way I could possibly have overcome such an obstacle.

Well done, the NMS!

Next time you visit Poulnabrone I hope you think of me and Charles Merrill!

Congratulations and well done, Mr De Luca.

Note: This article was first published in Vóg, our monthly newsletter in Nov 2017.