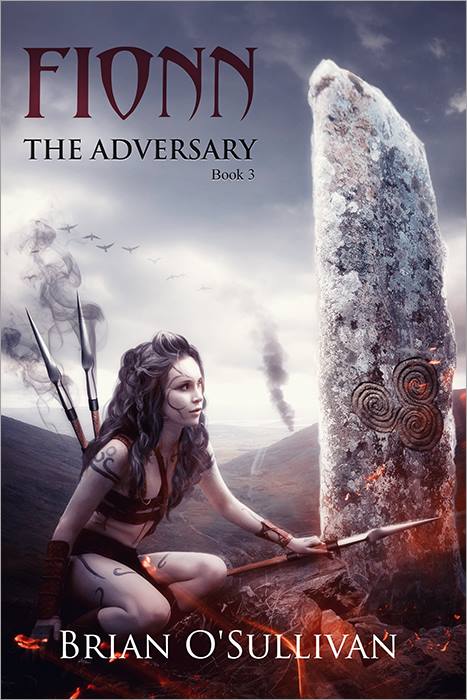

I really enjoy writing dialogue – particularly when it’s a dialogue between two strong characters with diferent motivations. This is a quick sample of a conversation between the woman warrior Liath Luachra and the bandraoi (female druid) Bodhmhall, who joined her hunt for a díbhearg (raiding party) in a slightly underhand manner. At this point in the story, neither character really trusts the other and that puts a nice tension in their interactions. This particular piece comes from Liath Luachra: The Metal Men which comes out tomorrow.

The converation occurs after a meeting to discuss the continued pursuit of the díbhearg.

A Conversation with Bodhmhall

With Crimall off reviewing the guards, it was Bodhmhall who represented Clann Baoiscne interests around the fire, sidling up silently to remain standing in the background and listening without comment. When the fénnid finally finished his story and the others started to drift away, she moved to approach the warrior woman, who’d seated herself on a fallen, moss-coated tree trunk a short distance from the others.

‘All power to you, Grey One.’

Liath Luachra eyed the bandraoi without warmth. Having spent the better part of the evening preparing defences for the campsite to counter a sneak attack by the díbhearg – a possibility she couldn’t ignore – she was tired and brittle and ready to sleep.

‘Your plan to find the díbhearg trail sowed the makings of success. To reap its bounty is your just reward.’

Reluctant to be snagged in further conversation, Liath Luachra let the compliment slide by without comment, however the bandraoi settled easily onto the trunk alongside her. She cleared her throat with a delicate sound, her refined and polished demeanour looking a little more ragged after several days of hard travel.

‘In truth, I didn’t like your plan. At the time, I didn’t believe it had the makings of success.’

This time, the woman warrior eyed her in muted surprise. ‘And yet you supported it.’

The bandraoi acknowledged that truth with a wry, slightly sardonic laugh. ‘I suppose I liked the alternative even less.’

A brief lull followed this forthright admission. Despite the lengthening silence however, the Clann Baoiscne woman showed no inclination to leave. Liath Luachra scowled.

‘Why are you here, Bodhmhall? Your warning in Murchú’s regard was appreciated, but we are not friends. Distrust, between your family and I, runs too deep.’

The bandraoi remained silent as she considered the woman warrior’s response. Finally, she terminated that quiet deliberation with a sigh.

‘Given your experience of Dún Baoiscne hospitality, I can understand your grievance, Grey One. And, yes, I acknowledge the loathing my father holds in your regard.’ The bandraoi winced. ‘Actually, he bears you a measure of hatred I’ve ever only seen directed against his most gruesome enemies …’

Liath Luachra gave a dismissive sniff. Tréanmór’s hostility held little interest for her. She was unlikely to encounter the rí of Clann Baoiscne again.

‘I suspect,’ Bodhmhall continued, ‘my father’s hatred stems from the fact he’s so rarely bested. When you defeated Cathal Bog, you upended the plan he’d orchestrated for your humiliation and turned it back on him instead. That took my father by surprise. That took everyone by surprise …’ The bandraoi paused then, as though struck by a sudden realisation. ‘Myself included.’

The Clann Baoiscne woman drew back a little, eyeing Liath Luachra with greater attention. ‘In truth, it confounds me to have overlooked someone of your complex potential.’

‘I’m surprised your tíolacadh revealed no raging blaze,’ the Grey One answered, and although her words were laden with sarcasm, Bodhmhall didn’t seem to take offence.

‘There’s truth in that,’ she conceded with grace. ‘Then again, you had me at a disadvantage when we first crossed paths.’

Liath Luachra regarded her carefully. She had no memory of meeting the bandraoi prior to her sly infiltration of the fian. ‘When we first crossed paths?’

‘At Dún Baoiscne. In the gateway passage. You were on your way to fight Cathal Bog.’

Liath Luachra studied the Clann Baoiscne woman’s features with new interest. She vaguely recalled another presence within the gateway passage at that time but, focussed on her imminent combat with the Clann Baoiscne champion, she retained no clear mental image of the encounter.

Bodhmhall patiently endured the scrutiny until the woman warrior finally shook her head.

‘I don’t remember you.’

To her surprise, the bandraoi chuckled at that. ‘Ah, you wound my vanity, Grey One. Am I so easily forgotten?’

‘I haven’t forgotten you’ve not told me what you want.’

The bandraoi frowned then, a new tightness of her lips suggesting a subtle reassessment.

‘Very well. I’ll spare you words daubed with winter honey. What I seek is forthrightness, forthrightness on the díbhearg we pursue. It seems to me that you’ve a greater familiarity with the raiders than you cared to admit to my brother – that, at least, is my sense of the matter. This pursuit is meant to be a shared endeavour between our two fianna towards a common purpose. In the spirit of that arrangement, I’d ask for a sharing with respect to the díbhearg’s true motivations.’

Only years of emotional compression allowed the woman warrior to conceal her true astonishment as she returned the bandraoi’s gaze. Behind that cool veil of impassivity however, she struggled to suppress a growing swell of panic. The Clann Baoiscne woman’s startling perspicacity had caught her completely by surprise and it was an abrupt and frightening revelation of just how dangerous she truly was. Crimall and Tréanmór might possess shrewd instincts that were enhanced by their ambition but Bodhmhall, with her piercing intelligence and An tíolacadh, was on level that far exceeded them.

The Grey One put her bowl aside softly and offered the ghost of a haughty shrug. ‘Given your reputed talent with imbas forosnai, I’d have thought you better placed than I to know the díbhearg motivations. Crimall certainly holds your Gift in great reverence and the Druidic Council are constantly at pains to assure us of the mystical glimpses An tíolacadh provides.’

Bodhmhall responded to the deflection with a bright smile but there was a subtle tension to her features that she couldn’t completely disguise. Behind her assured façade, it seemed the bandraoi had secrets of her own and the imbas forosnai ritual looked to be a topic she was reluctant to broach.

To the Grey One’s surprise, Bodhmhall abruptly rose to her feet. Although it appeared at first that the Clann Baoiscne woman intended to stalk away, she stood watching the woman warrior, the flickering of the fire casting a strange set to her features.

‘Sadly, on certain subjects Crimall tends to greater conviction for things he’d like to be true than in the truth itself. The reality is that An tíolacadh’s not a Gift so much as a burden. That’s doubly so with the imbas forosnai ritual, despite what Na Draoithe would have you think.’

She paused then, and Liath Luachra regarded her warily for there’d been a weary honesty to the response she hadn’t anticipated. More importantly, there’d also been a tacit acknowledgement in the bandraoi’s eyes, a kind of diplomatic retreat or implied agreement not to pry into the woman warrior’s secrets if she chose to respond in kind.

The bandraoi made to leave but then paused in mid-step, turning to consider the woman warrior over her right shoulder.

‘I’ve told you the full truth of why I’m here, Grey One. Perhaps you’d reciprocate that with frankness of your own. Why are you here? It’s obvious you take no pleasure in leading this Seeking.’

‘There’s no secret to that, Bodhmhall. I’m here because Murchú asked for my help.’

‘For your help.’

‘To rescue his sister and deal to her abductors.’ She hesitated. ‘And perhaps to kill some ghosts of my own.’

‘You cannot kill a ghost, Grey One.’

‘Perhaps not, Bodhmhall. But I will surely give the matter my best efforts.’