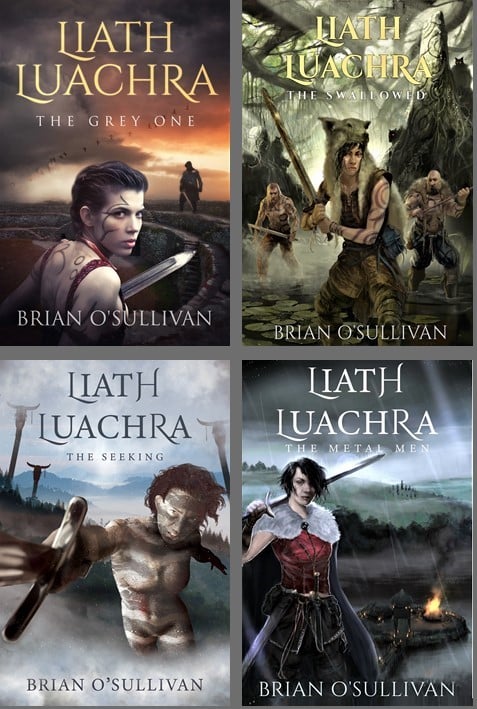

This is a scene from the upcoming novel ‘FIONN: The Betrayal‘ (although that title is likely to change).

Set in the settlement of Ráth Bládhma, in this scene, the woman warrior Liath Luachra, is attempting to plan a dangerous trip to the distant Tailte Méithe – The Fat Lands.

To do this however, she needs information from the punacious techtaire (messenger) Feoras -and a conversation she has not been looking forward to.

Leaving the firepit, Liath Luachra worked a path between the roundhouses, slowly making her way to the southern side of the ráth embankment and the lean-to where Feoras was sequestered. There, despite the mildewed light and the lean-to’s interior shadows, she had little difficulty making out the sour puss on the techtaire as he watched her approach.

Cónán, standing guard to the left of the lean-to, rolled his eyes and shook his head as the Grey One drew closer. The previous evening, the young warrior had expressed his weariness at the techtaire’s incessant complaining. According to Cónán, when Feoras wasn’t bitching about the food, he was carping on about the accommodation, neither of which he considered commensurate with a messenger of his standing. His treatment at Ráth Bládhma had drawn particular vitriol, although there at least Liath Luachra felt he might have had some grounds for complaint given that, on their return to Glenn Ceoch, she’d drugged the cantankerous old man and transported him on a litter, to conceal the settlement’s location. When the techtaire had finally come to, he’d been furious to learn what she’d done. Bizarrely, that fury towards her had been exceeded by his fury at the ignominy of being billeted in a lean-to used for the storage of winter fuel.

It was hard to know where the techtaire’s delusional expectations of hospitality might have come from, but Liath Luachra had little interest in trying to find out. As she slid in under the shelter’s slanted roof, she ignored his scowling features, quietly grabbing a nearby stump of wood and rolling it into an upright position. Sitting herself on the makeshift seat, she shifted around so that she was facing the old man directly.

‘We leave Ráth Bládhma tomorrow,’ she said bluntly. Feoras wasn’t a nice man so there seemed little point in social niceties.

The techtaire’s scowl softened a little at that announcement.

‘You’ll hear no complaints from me,’ he answered haughtily, raising one hand to ruffle his thick bush of white hair. ‘Arriving at Ráth Bládhma has been akin to stumbling upon a precipice marking the limit of human influence. My welcome has been nothing but a litany of insults and injury. My hospitality, little more than cast-offs a mottled swine would reject.’

He waved a hand to indicate the cramped, wood-strewn interior, as though to support the validity of his grievance. Liath Luachra said nothing, waiting for him to complete his querulous griping before she proceeded to the reason for her visit.

‘We’ll leave Glenn Ceoch at first light. By then, the final preparations should have been completed. More importantly, that allows a full day for the ground to firm up after last night’s rain.’

Feoras’ forehead creased a little at that. He pursed his lips and squinted at her uncertainly.

‘If the ground is firm,’ she explained, ‘we leave less trace of our passage on the Great Mother’s mantle. Tracks become less important the further we get from Gleann Ceoch but with Clann Morna haunting the nearby hills, I’ve no desire to leave a trail that leads straight back to the settlement.’

The techtaire scratched at his beard but made no comment.

‘Before we leave,’ the woman warrior continued, ‘it would suit my purposes to learn what you can tell me of the character of the land we’ll be traversing, any relevant water sources, impassable rivers or other obstacles …’

Her voice stalled momentarily as she registered the particularly sour expression he’d turned towards her, but she continued with fresh resolve.

‘That knowledge would allow me to take proper account of the supplies we’ll need.’

‘The Cailleach Dubh has agreed to follow my guidance,’ the techtaire countered, his jaw jutting forward with mulish obstinacy. ‘It should be my role to decide on what might be needed over the course of our travels.’

Liath Luachra regarded him coldly.

‘The argument was lost before it even started, Feoras. I lead the travel party. You’re a guide, Nothing more.’

The old man glared at her, but the heat of that glare glanced harmlessly off the smoothness of her serene, somewhat remote features. Defeated by that unruffled composure and the finality of her response, he turned his angry gaze away.

‘Well?’ she prompted.

She noted the techtaire’s jaw clench a little and, for a moment, she thought he was about to sink into an outraged sulk. To her surprise however, he seemed to think twice about it for when he spoke again, his voice was smooth and calm if, troublingly, cordial.

‘What is it you wish to know?’

Note: FIONN: The Betrayal should be available in May/June 2024