Like many other Western countries, poets, politicians and artists in Ireland also fell into the trap of trying to personify their nation, that is, trying to characterise the concept of the country as a person, usually a beautiful young woman.

Such personifications are mostly restricted to the western world and were most popular in the late 19th and early 20th century. Usually, they tended to be used by governments in times of upheaval to ‘bolster’ the population when that nation was at risk (or portrayed to be at risk) from other influences. This is why most of the personifications are actually quite militaristic in their visual manifestations (they were often modelled on female war goddesses). If you look closely at the classic examples such as Britannia (England), Germania, (Germany) Marianne (France) and so on you’ll see they all carry weapons.

In Ireland, things were slightly different in that our first national personifications were usually a helpless young woman of great beauty (or an old woman) beset by oppressors. This is probably because they were created from a subjugated society as opposed to an oppressive (and foreign) government. Certainly, they were all intended for propaganda purposes but at least the independent earlier creations had (slightly) more depth than those military representations used by the latter.

The personification of Ireland as a nation originally started with the Aisling (Dream) poetry genre produced by Gaelic poets such as Aodhagán Ó Rathaille and Eoghan Rua Ó Súilleabháin from the mid-to late- 1600s right up to the late-1700s. In these poems, Ireland is represented as a young woman/old woman (generally referred to as ‘spéirbhean’) who lament the excruciating existence of the Irish people and prophesises the imminent coming of heroes to save thsem. They were very much political poems, of course. By the mid-1600s, most of Ireland was pretty much under the military yoke of the English Crown and the Penal Laws (forbidding many basic Gaelic cultural expressions) had been introduced. This, then, was the Gaelic poets’ attempt at rallying the people and giving them hope against the invaders.

Unfortunately, of course, the heroes never came. All elements of Irish military resistance were overcome, the English Crown secured complete control of the country and over the next four hundred years the Gaelic language and culture was substantially eroded.

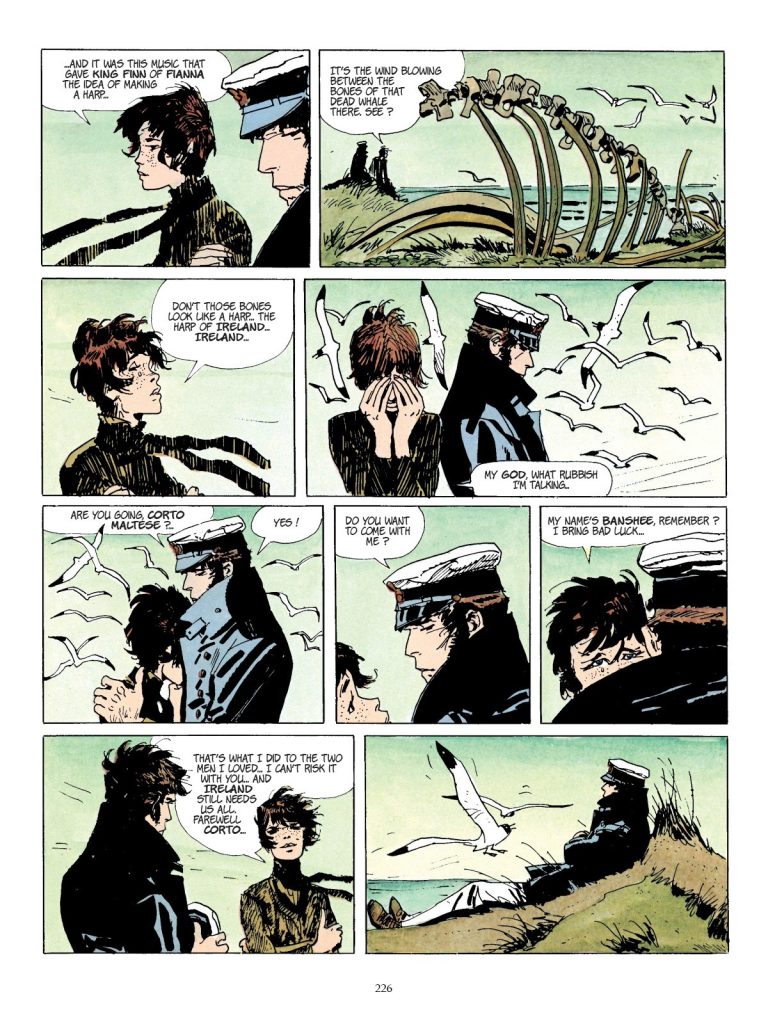

As with all oppressive regimes, however, rebellion and nationalised sentiment fermented and arose once more, particularly towards the start of the early 20th century. By then, of course, Gaelic culture had been largely eradicated but in an effort to revive some of the old traditions, the Aisling poems were brought out and dusted off. The original 16th century Irish spéirbhean was updated and reframed into more contemporary versions such as Róisín Dubh (by the likes of James Mangan and Pádraig Pearse) or Cathleen Ní Houlihan (by WB Yeats and lady Gregory) in 1902. Ironically, the English Punch magazine introduced their own version (called Hibernia) around this point but it never really took off back home.

Cathleen Ní Houlihan

Cathleen Ní Houlihan

Following the Easter 1916 rebellion and the War of Independence, the Anglo-Irish treaty was signed. Keen to have its own national personification to show how unique and different this new country was, the Irish Free State government immediately mimicked other countries by inviting an artist (Lavery) to create one for the new Irish banknotes.

John Lavery was something of an anomaly and an interesting choice for creating the national personification picture. A Catholic-born painter (from Belfast), he’d been offered the post of official artist for the British Government during the First World war and later awarded a knighthood. Lavery was a rare individual in that he was equally at home in both the English/Protestant and Irish/Catholic/nationalist camps. With a foot in both, he must also have been one of the few people of his time to be made a free man of both Dublin and Belfast.

Lavery used his wife (Chicago-born, Hazel Martyn – also known as Lady Lavery because of her husband’s title) as the model and its her likeness on the personification of Ireland that’s probably the most well known today. This likeness was reproduced on Irish banknotes from between 1928 until the 1970s but when these were superseded, it continued to be used as a watermark on some notes until the euro was introduced in 2002.

In conclusion therefore, the personification of Ireland is a painting of an American woman created by a Belfast-born Catholic and based on a 20th century regurgitation of a 16th century Gaelic poetry concept.

In an odd way, that seems to quite accurately summarise where Ireland is today

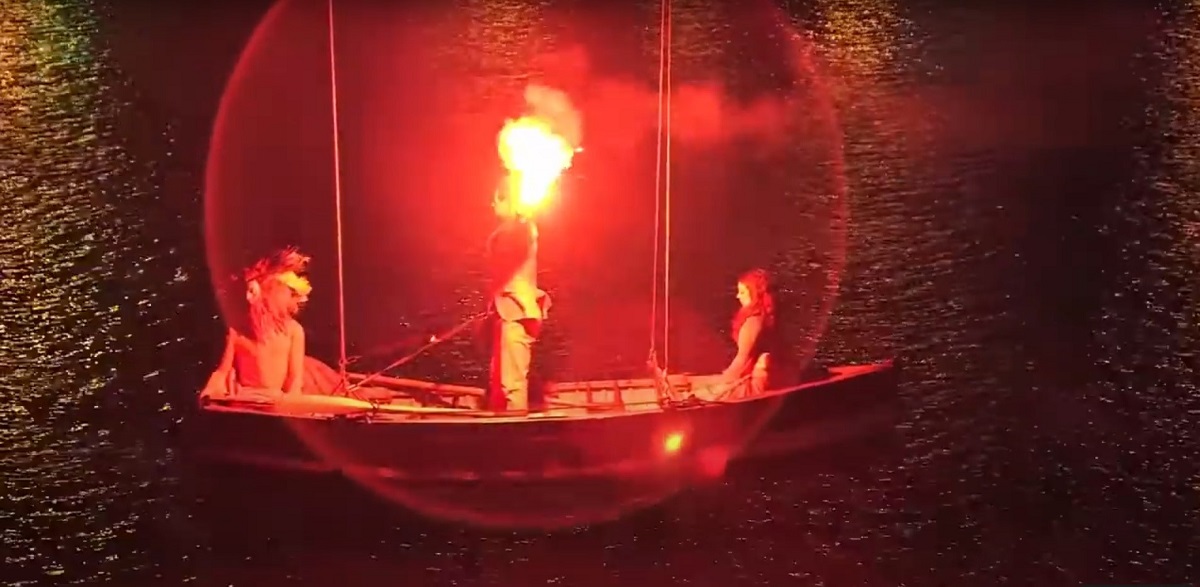

Cathleen Ní Houlihan

Cathleen Ní Houlihan